PROJECTS

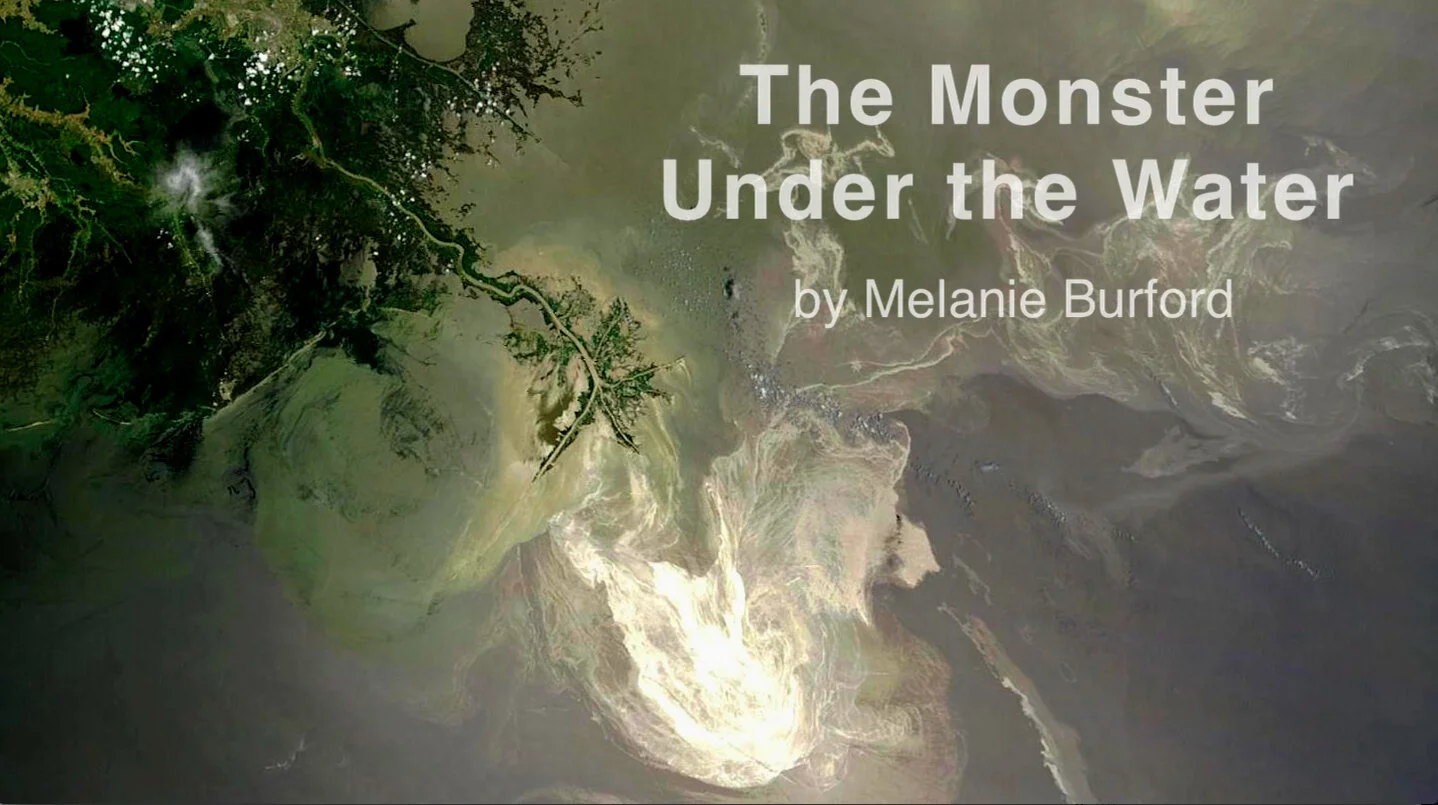

The Monster Under the Water

By Melanie Burford

Jason Melerine was born to the water. His father fished, his grandfather fished, his great-grandfather fished. At age 11, Melerine drew pictures of the boat he would someday own. The day he turned 16, he quit school to go crabbing. Now 28, he can barely read and write. Fishing off Delacroix Island, a sliver of land alongside the Louisiana coast, is all he knows.

In the first weeks after the Deepwater Horizon rig exploded April 20, 2010, Melerine, like most Louisiana fishermen, feared the worst: that the cocktail of oil and dispersant would immediately kill the state’s already fragile fishing industry. His worry consumed him. He pulled patches of hair from his chin and his leg. He landed in the hospital with migraines. He contemplated suicide.

“For us, it’s a life, it’s what we love to do,” said Melerine, whose four children eat crab so often they complain about it. “It’s what we know to do. Water is my life.”

The story of the Gulf oil spill has often been told through numbers: more than 200 million gallons of oil spilled, more than 1.8 million gallons of dispersant dumped on top, more than $16 billion spent by BP on cleanup, claims and other spill-related bills. The human toll is more difficult to pinpoint, which is why ProPublica took a longer look at what happened to the fading fishing community of Delacroix, an island romanticized and mispronounced in Bob Dylan’s “Tangled Up in Blue” and treated as a nostalgic touchstone by writers who marvel at people who continued to live off the land and the water, passing skills from father to son.

Despite the fishermen’s fears, the worst didn’t happen. The oil never coated Delacroix Island, and it didn’t hit the surrounding parish waters nearly as much as predicted. The well was capped. BP seemed to pay whatever money was asked. Scientists declared the seafood safe. The country moved on.

But for the fishermen of Delacroix Island, moving on hasn’t been so easy. All the old uncertainties about their declining community — hurricanes, erosion, the intrusion of modern life, falling seafood prices — are still with them, but now new uncertainties are piled on top, underscored by the recent deaths of dolphins along the coast and crabs off Delacroix Island. Even if nature somehow rights itself, the BP money that has flowed to the Delacroix Islanders may have inadvertently hurt their community and market by encouraging some fishermen to stay home. The fishermen ask themselves about the future and worry that they may be the last of their kind. Some have taken anti-depressants and sleeping pills to cope with the stress.

“I guess they been taking care of us all right, but they done tried to cover it all up with money,” Melerine said in November. “Money don’t take care of everything. We might be living it up now because we got money. But three years from now, we might not have nothing. We might not be able to sell nothing. This oil’s gotta affect something.”

Publications

Gulf’s Delacroix Islanders Watch As Their World Disappears, ProPublica

BP payouts create ‘spillionaires’, The Washington Post