PROJECTS

Aqui Vivimos

By Dominic Bracco II

Angelica Ortiz collapsed on the asphalt outside the morgue’s single door. The sun dried her tears. She lifted herself up to glance through the small glass window as if to check if he was still there. Inside her ten-year-old son lay on a cold steel gurney. She fell back down to her knees. Her husband still didn’t know. She was alone but for a small crowd of journalists who stopped to take her picture. Renato Lacayo, a Honduran journalist, stood back and watched them.

He watched, nursing his left arm, cradling it with his right. A few days before he’d smashed it during a football match. The game was played in a rainstorm. They lost. It was the first game his team Los Hurricanes had lost in ten years. The night before the game he got drunk with friends. He spoke on the phone with his wife when he got back to the hotel from the morgue; he didn’t tell her what had happened.

Violence has become so commonplace in Honduras that it’s become the norm rather than the exception.

For years the social classes of Honduras have lived in two worlds where those with money retreated behind concrete walls with armed guards, and those who don’t live amongst Las Maras who killed indiscriminately. In 2009 a coup d’état set off a surge of violence that’s touched everyone. Tellingly, when the Honduran military staged the coup, America looked the other way.

It’s no surprise that the country imploded. Former President José Manuel Zelaya was ousted while attempting to change presidential term limits and beginning to enact reforms that would examine land sales from poor farmers to rich land barons. The topic has split the country in two political camps, where right wing capitalists lean toward a less equitable society and leftists use the assassinations that surround land rights squabbles as fuel for their increasingly Chavista movement. Today 60 percent of Hondurans live in poverty.

“Success” in Mexico has pushed trafficking through Honduras. Three quarters of all U.S. bound cocaine now passes through Honduras. The US has reacted by placing three operating bases there, in addition to its air base, to practice drug interdiction.

The tiny country of 8 million is the world’s most violent country. Gangs control entire cities. Campesinos war with corporate funded paramilitary groups in the east. Warring cartels massacre entire villages in La Mosquita. In the capital Tegucigalpa violence has become more sporadic and faceless. Random crime has increased. Car jacking, robberies, and assaults are a daily occurrence. San Pedro Sula, the country’s industrial center, sees an average of 19 murders a day.

The shoot out between police and an extortionist that killed Ortiz’s son was only a roadblock in the day’s activities. Hours later as flies gathered on the extortionist’s body, merchants walked through the crime scene, at times without even turning to look at the dead man laying facedown on the sidewalk.

The normalcy of violence in current Honduran society is extremely troubling and yet it is understandable. As a journalist who has covered violence for five years, there is something unnerving in its consistency. The lack of coverage Honduras receives is astounding, particularly for a country considered one of America’s last friends in Latin America.

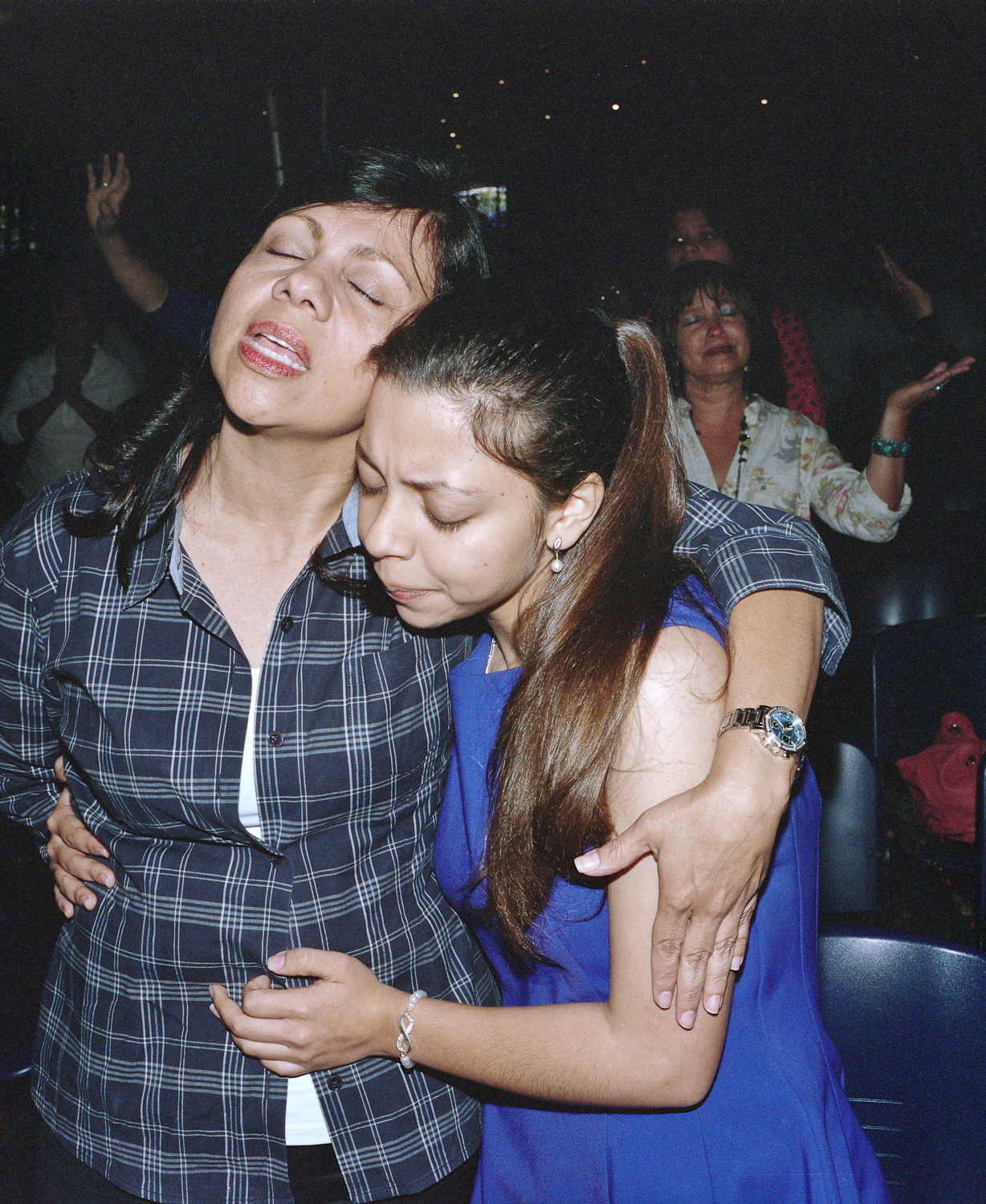

And yet despite the violence, life goes on. Teenagers build a skatepark in Mara territory. Psychedelic bands play in Tegucigalpa. Moneyed Hondurans shop in the country’s malls. Tourists flock to Honduras’ islands and resorts. American missionaries build schools. The circus performs in San Pedro.

My interest in Honduras started nearly seven years ago when I found a Honduran woman laying under a mesquite in South Texas. She’d been separated from her group and was lost out there. She’d been walking for three months. The rancher told me to back away from her because she was sick while he dialed the Border Patrol. She begged me to help her, but I didn’t know how I could. I was already a journalist. My uncle had been in prison for trafficking. I thought to myself, “What kind of place would drive someone to come all this way risk death here in this desert?” Seven years later a friend and I took our savings and finally went. What we found was as beautiful as it was terrifying.

Honduras is one of the most under reported stories of our time. Those stories that are done often ignore the root causes: deep political rifts that mimic those of earlier Central American wars, widespread poverty, extreme gloves off capitalism, private foreign interest, and the extreme corruption it produces. Aqui Vivimos explores these ideas and looks at daily life, the contrast between beauty and horror, and the often-surreal landscapes, and personalities it produces.

(Written by Dominic Bracco II and Jeremy Relph)

Publications

A Contested Election in Honduras, The New Yorker

Tracing the Dark Roots of Border Smuggling, National Geographic PROOF